Creating is difficult and demanding work. Ask any creator. We know it requires a synthesis of imagination and high technical skill, but we frequently forget that the act of creating is also allied to humor and play. Play is thought of as a childish pursuit, not appropriate for adults in an increasingly technological and empirical world. There’s a story about a man who explains to his little daughter that his job is to teach adults to draw. “You mean they forget?” she asks. Yes, they do. So, before we go further into the meanings of creativity, I’d like to invite you to come play with me. Sometimes it is challenging, but as often it is great fun.

I’ve been a close observer of my grandson, who has just reached his early teens. Over the years I’ve been enthralled with his rich and deep imagination, and his ability to invent fantastic “special machines” meant to accomplish all manner of tasks. David is a 21st century child, aware of much of the technology with which we live. And while I have delighted in his endless imagination, which, incidentally, has helped to stimulate my own, I could also feel his frustration at not having the executive skills to realize his fantasies.

So this is the tipping point, where, as they grow up, children are rewarded for empiricism and “the right answers” and increasingly encouraged to avoid fantasy and risk. It’s the real world. Even in California, as close as we are to the innovations of Silicon Valley, in public education there seems to be an inverse proportion in emphasis between imagination and executive abilities. We need to have both. And we have to recognize that frustration is a gift, admittedly well disguised, an obstacle which rewards those who overcome.

When I have taught courses at arts institutions on the creative process using the medium of photography, the last thing I could possibly have thought of was to begin - or even end - with discussions of cameras and lenses. I would enter the classroom and ask my students for a description of their equipment, and hear “Canon,” “Nikon,” Olympus” and other manufacturers. It was a trick question. What I really wanted them to be aware of was their own natural equipment, their senses, their brains, their anatomy, their acculturation and education. That’s the real photographic equipment. That’s the real equipment of the painter and the author, not the brush or the pen. It’s why I called the course The Eye’s Mind.

I have little interest in the mechanics, and great interest in perception and understanding the narrative of pictorial language. Were I to teach a class on cooking, would I really begin with the anatomy and function of stoves and pans, rather than with nutrition and taste? That’s what manuals are for. Let us not be boring.

For my students, their first assignment was to bring to class one or two pictures found in magazines, books, catalogues, even family albums that fascinated them, and discuss them. Getting them enthusiastic about images was the engine that drove their enthusiastic acquisition of technical ability so they could author their own.

My friend, photographer Lady Ines Roberts, once told me that her engineer husband, Sir Gilbert, a delightfully smart, kind and generous-spirited man, invited her into his office and drew diagrams on the whiteboard of the focal length and acceptance angles of lenses, “thereby retarding my progress for two years.” At exhibitions of my own work, it’s always a man, never a woman, who approaches me with a compliment “I love your work,” and immediately follows with “What kind of camera do you use?” In a jocular moment, Brooks Jensen, the editor/publisher of LensWork reminded me that “When you buy a camera, you’re a photographer, and when you buy a violin, you own a violin.” Mechanical instruments, however necessary, should not be confused with artistic expression.

Creation requires the willingness to be thought of as foolish, often wrong, and to value the words of our critics. It takes considerable courage. Think of it as a kind of exploration, where the process and the ends are uncertain. There are no maps. Innovation requires the defeat of habit. We are an explorative species, but we also seek the comforts of revealed truths and established taxonomies. When I was new to photography, I kept hearing about the compositional “rule of thirds,” in which a rectangular field is subdivided into nine segments, with the idea that any element of significance should be placed on one of the four internal intersections to make the greatest visual impact. My mental compass rebelled at the thought of this prepackaging. It was happily supported not only by looking closely at many images and reading the stories behind them, but by Leonardo’s words in his Treatise on Painting: “Those who create by rule, create nothing but confusion.”

What really counts is the intellectual bridge between artist and audience, what Arthur Koestler in The Act of Creation called “the magic synthesis.” That synthesis depends on the ability of the artist to hold and guide the attention of the audience, often with the interruption of logical flow. That’s the connection to humor and play. Is it possible to experience the work of inventive comedians, surrealists, cartoonists, playwrights and architects without knowing that our senses are being tweaked and therefore intrigued?

For those who wish to explore the subject of creativity more fully, there are fine books by Robert Grudin (The Grace of Great Things), psychologists Rollo May (The Courage to Create), Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Creativity), and that delightful read by photographers David Bayles and Ted Orland, Art & Fear. You may also be interested in my own essay for the Royal Photographic Society and LensWork, Creation: A Journey to the Reflecting Pool.

Innovation breeds innovation. Let us play.

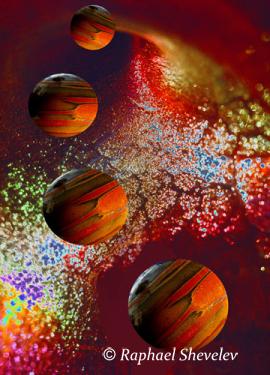

(Click on the embedded image to see the story)

__________

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, and known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Comments

These are really important

These are really important ideas Raphael, and beautifully expressed. It's so wonderful that you have this blog to share with the world.

I love what you have to say.

I love what you have to say. Every time! I've just shared this article with my writers'/critique group because even though you're in the visual arts and we craft with words, the goal is the same. Thank you!

This recalls to mind the

This recalls to mind the opening sentence of Huizinga's "Homo Ludens" (Man the Player): “Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.”

I wish I could have taken a

I wish I could have taken a course from you. Maybe it would have unleashed some creativity that seems to be lacking in my life.

It's typically generous of

It's typically generous of you, Raphael, to provide us with stimulating bibliography -- but I think you've really summed it up yourself when you said that the real tools of creativity are our senses, our brains, and our educations. And of course that last component is one we have unlimited power to strengthen and refine.

Thank you so much for this

Thank you so much for this magnet to the real source of art. I've been drawing, painting

and designing for as long as I can remember - now that I must learn computer drafting to express my architectural self, I'm experiencing an exciting glow in computer tech. and with your writing I'm also reminded of the advice from a past painting teacher: "Yes, learn the technique, then throw it away and express yourself." Thanks again Raphael for your excellent writing and inspiration!

I agree with Chris. This is

I agree with Chris. This is a keeper to be read freshly from time to time.

Your grandson, David, is an

Your grandson, David, is an extremely fortunate young man! When I think of what I could've achieved if I'd had an influence in my life like you! (Well, now, I have!...)

As one of the 15 - 20%

As one of the 15 - 20% membership of any photo organization I have been part of, I have noted that men generally want to talk about the latest gear and women tend to talk about what their latest photographic project is. I am generalizing, I know. It is not always this way but does go to the heart of what is most important but perhaps hardest to get at – our creativity and how to access it. And freedom to play.

I had an experience years ago that was pivotal for me. I took a paper-making class a my local community college because I wanted to explore coating photographic emulsion on my own paper. I had a wonderful instructor but was initially a bit daunted by her teaching style. Coming from years of traditional photographic training and practice, where generally there is a precise correct answer, I expected the same when exploring the challenges of paper-making. My instructor's simple answer to all of my questions was, "Try it. See what happens." After grumbling, I took her advice (what else could I do?) and it has come to be very freeing. No across the board right answers, just what feels right for me and trusting in that. Also, mistakes are OK – always informative and sometimes lead to a new direction. So, yes, let us play!

Post a new comment