My European refugee parents had ambitions for their only child.

Mother wanted a doctor, and bought me a stethoscope for my twelfth birthday. It provided an opportunity to examine my friends, boys and especially girls, able to give optimistic diagnoses except in the case of my friend Harry, with whom I accomplished a medical miracle by diagnosing gonorrhea. I wrote the word down for him. I still don’t think I deserved the vicious scolding from his mother. I gave the stethoscope away.

Father, noting his son’s penchant for argument, aggressively insisted on a law career, and it took begging “Uncle Ben,” the Dean of the Law School, to persuade Dad that I had no such interest.

What I really wanted was so far from parental imagination that I might as well have insisted on becoming a photographer, a writer and an opera star. I had lost my way in the arts, an area entirely alien to my parents.

I loved singing until my voice broke and dashed my dreams of becoming the next Caruso. I liked noodling around on the piano, inventing new cacophonic chords, which on rare occasions resolved into acceptable majors and minors, giving my parents scant if desperate hope.

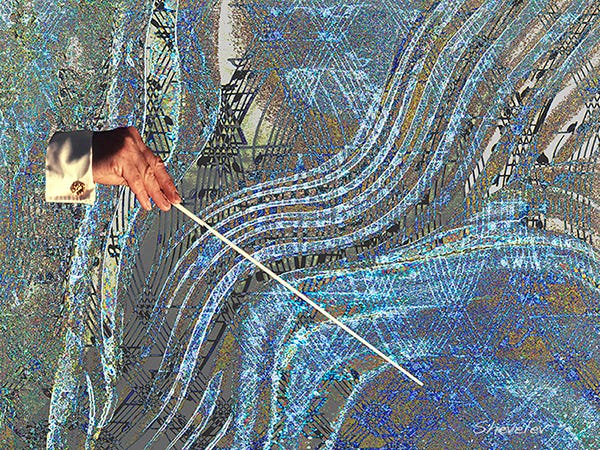

My passion for great classical music was further propelled by exposure to the Symphony Orchestra and a friendship with the conductor, who tried to teach me on the only instrument I could hope to master, the baton, which has a certain megalomaniacal attraction.

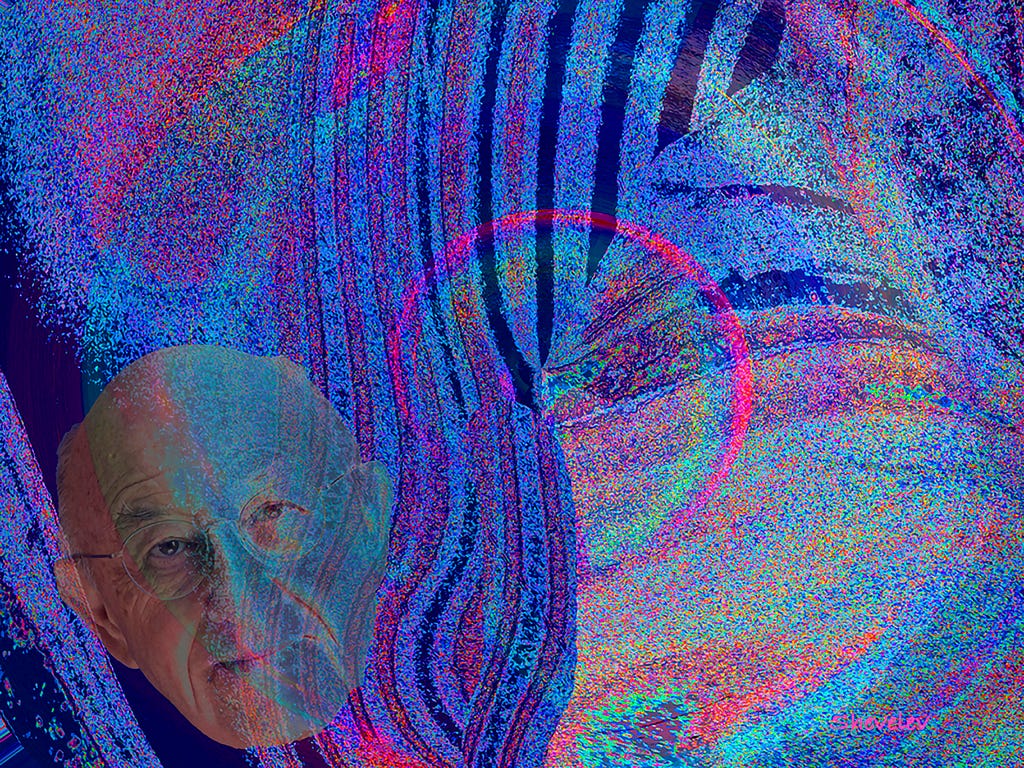

A compromise was reached when, at the University of Cape Town, I read politics, philosophy and economics, the latter pleasing my father who hoped I would save more and spend less. But although I continued those studies in graduate school in America, and enhanced my parents’ social cred when I became an academic — “Our son, the Professor” — I still felt a gap in my life, most keenly when I visited art galleries and museums, and fell in love with impressionism and surrealism.

In midlife I married a woman of great intellect and immense love, and finally dared, with her full support, to return to my passions and become an artist and writer. She said, “If you want to do it, do it!” And so I did.

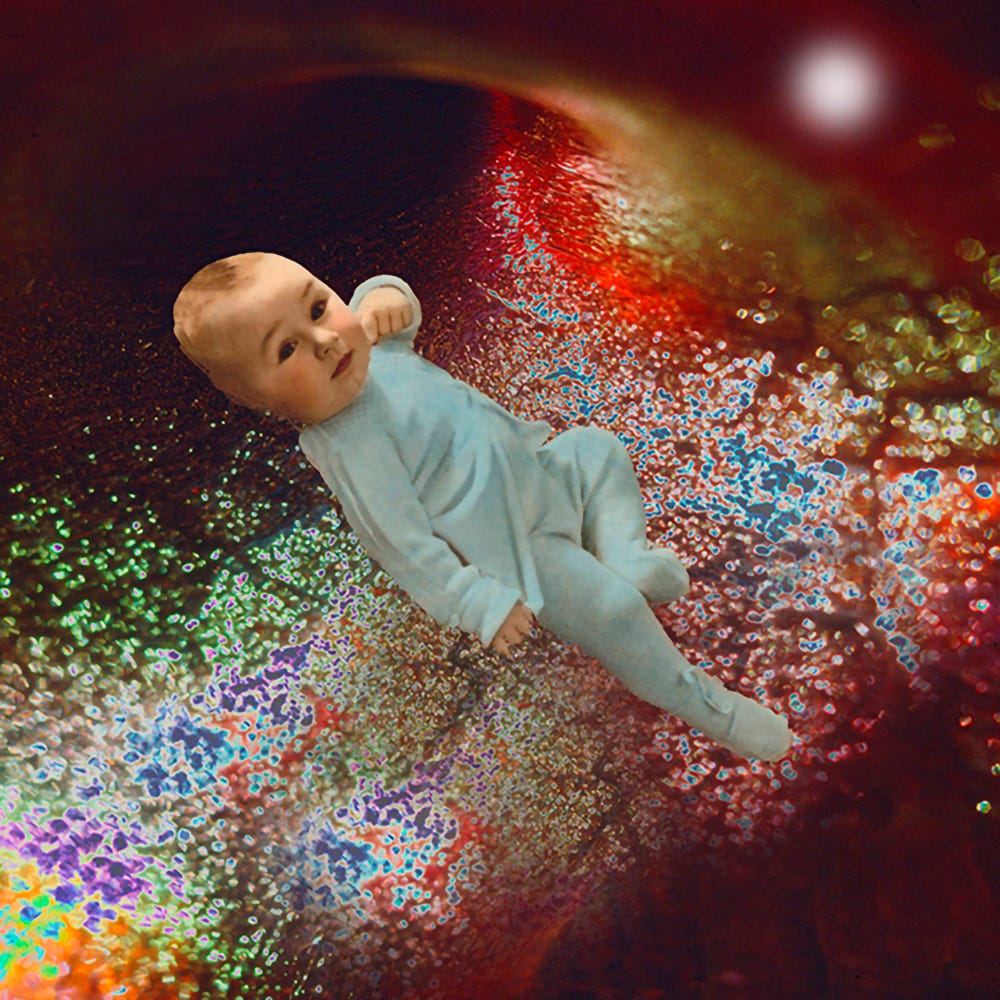

Now, facing the prospect of my eightieth birthday on December 10, 2018, I’ve decided on an alternative autobiography, expressed in three images:

______________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on the creative process. He is a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain. He is known for the experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Still Dazzled was originally published in Pandemic Diaries on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Post a new comment