In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, my father would occasionally bring home from the synagogue on Friday nights a person or couple who had survived the Holocaust.

In the warm South African summer of 1945-6, I saw a number on a dinner guest’s arm. When I asked him about it, he looked at my mother and she gave a barely perceptible shake of her head, so a child’s question went unanswered. My parents were then, and remained thereafter, quite remarkably silent about the catastrophe. Curiosity was partially satisfied when I began to sing in the choir of the Vredehoek Synagogue, and on the single time I can recall him rolling up his shirtsleeves, I saw a similar number on the arm of the Cantor, Jakob Lichterman, a Polish refugee whose fine lyric tenor voice and sweet temperament remain pleasant memories. I didn’t find out much more until my freshman year at the University of Cape Town, a time of wonderful intellectual opportunity both inside and outside the classrooms. It left me, then as a student, and later as a professor in the United States, with the clear understanding that lecture halls are just a fraction of where learning occurs.

I spent much of that year in the basement of UCT’s Jagger Library, reading the newspaper stories of the events from British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s signing of the Munich Agreement in the year of my birth, 1938, to the surrender of German armed forces to Field Marshal Montgomery at Luneberg Heath in May, 1945. Some of my formal academic work was neglected, in favor of an education about the numbers on victims’ arms. Almost a decade after graduation, I introduced a course on race as a factor in international relations at the University of California, Santa Barbara. I’d had good preparation: the son of fugitive European Jews, raised in apartheid South Africa.

In 1946, a young American couple from Chicago, Howard and Elsie Schomer, accepted an invitation from Pastor Andre Trocme to help with postwar reconstruction in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a French village on the plateau west of Lyon. They took their infant daughter Karine along with them, and stayed there for ten years. The story of Le Chambon is now well known. During the years of the Second World War this largely Huguenot village offered refuge, and therefore life, to about five thousand Jews escaping from the predations of the Nazis. In what Philip Hallie in his book Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed, called “a conspiracy of goodness,” the heroic rescue was presided over by Pastor Trocme and his wife Magda, and the center of it all revolved around the Protestant church, the temple.

It is a sacred place for Jews, too, and indeed for all humanity. The story has also been told in the film Weapons Of The Spirit, made by family friend Pierre Sauvage, once one of the rescued children, and by a more recent book, We Only Know Men: The Rescue of Jews In France During The Holocaust, by my friend, Patrick Gerard Henry, Emeritus Professor of French at Whitman College, Oregon.

Howard Schomer worked as one of the drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948. South Africa and the Soviet Union abstained. In later years he would serve as President of the Chicago Theological Seminary, and in 1965 walked with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the march on the bridge at Selma, Alabama. I first encountered my future father-in-law when I saw the documentary footage of the march.

I have spent the last twenty-five years largely in the pursuit of photography and writing, and have made thousands of images in the Americas, Europe and Asia, as well as many “conceptual-art” pieces constructed for the purpose in my studio. So I’ve decided to nominate one of my own images as my personal icon.

Famous artists usually have art historians nominate theirs. For Pablo Picasso, it is probably Guernica, for Marc Chagall, perhaps The Violinist, for Ansel Adams, Moonrise over Hernandez, New Mexico. My latest reading includes Anne-Marie O’Connor’s brilliant volume Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Thus, for Klimt, that is surely his icon. Mine was unexpectedly made in a little village in France.

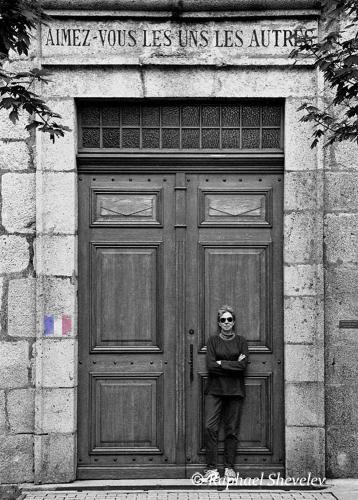

In 2001 I accompanied Dr. Karine Schomer, now my wife, to “her” village. The temple has none of the grandeur associated with the great cathedrals and churches of France. It is, in fact, a simple stone box, but in that box there was, at a time of great need and terrible danger, a spirit of humane commitment far beyond even the words engraved above the doorway, the great injunction from the Newer Testament,“Aimez-Vous Les Uns Les Autres,” Love One Another.

I made the accompanying picture of Karine there. The iconography is simple: a relaxed, confident, strong woman, raised in an atmosphere of deep commitment to human rights, before the unyielding square stone geometry of that particular Huguenot church with its heroic congregation. On her right, at face level, I added a worn, painted graffito of the bleu-blanc-rouge, the French flag. It is as worn and scuffed as was the honor of France during the war years. Le Chambon was the village that accomplished so much to rescue that honor.

I therefore use two names to identify the picture, and they are both entirely apt: “Aimez-Vous” and “L’honneur de la France.” The picture contains so much that is dearest to me. This is the picture that brings me home to my own values. It is my icon.

_________________

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Comments

As always, your stories and

As always, your stories and images are beautiful, insightful and inspiring. If I could have one microcosm of your eloquence I would be a lucky person. Thank you for sharing all of this.

Very eloquent and touching!

Very eloquent and touching!

Thank you, Raphael, for the

Thank you, Raphael, for the wonderful photograph -- I aspire to be such a relaxed, confident, strong woman as the one in that picture! And for the story that led you to make it. It is an icon, indeed, in these days when fear and self-interest still keep so many from being able to reach out to 'one another'. But it gives me hope! and also gives me a little smile, seeing your own hand in the 'tricolour' graffito. A note that says that only when nationalism is derived from love and generosity of mind will the future be ensured.

Dear Raphael, your heart is

Dear Raphael, your heart is so full and so in the right place.

This is the time for such

This is the time for such events and stories to be told, as our world is seeing so much of the same animosity and hatred, based on absurd religious perversions and twisted racial bias. This serves as a stark reminder that greatness is enveloped in the simplest of human gestures, caring for and truly loving one another, in word and deed. The heroics of the obscure saints in Le Chambon deserve retelling in churches, synagogues, and mosques around the world... for no other reason than to show that love can truly prevail in the face of the ugliness of human depravity. Thanks for sharing your story... and your heart!!

I love the picture of Karine

I love the picture of Karine and your statement about your icon. Plus the art on the website is very impressive. My book "We Only Know Men" that you kindly mention was translated by a Trocme, Helene Trocme-Fabre, and published in French as "La Montagne des Justes" in 2010. I have been working for more than two years on editing a volume which will be published as "Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis" by Catholic University Press in Spring 2014.

You have such depth of

You have such depth of feeling and a magnificent ability to display it. This photograph says so much. In reading what you wrote and out of the corner of my eye seeing parts of the image coming forth, on my left, there was a strong feeling of power and peace and love developing. You not only write with total elegance, you create the same in your photography. I feel fortunate to have you as a friend.

Last Sunday, we attended a

Last Sunday, we attended a presentation at our UU church by Rianne Eisler, author of "The Chalice and The Blade" and "The Real Wealth of Nations." She talked about the need for cultural transformation and suggested that one of the ways to do this is by "changing the conversation" from one that is informed by domination values to one that is inspired by love and partnership. Both your essay and image do just that.

Post a new comment