We owe to composer, musicologist and satirist Peter Schickele our profound gratitude for having discovered his alter ego, P.D.Q. Bach, “the youngest and stupidest of the Bach children.” Quoting from memory, with appropriate apologies, “In an age when it was common for composers to steal musical ideas from each other, P.D.Q. Bach was the only one who used tracing paper.”

But he was not the last. As a photographer, I see remarkable attempts at trying to become P.D.Q. Adams, P.D.Q. Bullock, P.D.Q. Cartier-Bresson, P.D.Q. Lange, P.D.Q Leibovitz, P.D.Q. Mann or P.D.Q. Kenna.

Michael Kenna and I have discussed the extraordinary number of Kennites, who try to intervene in the integral process of cause (the artist’s conception) and effect (the artist’s final product) by attempting to produce only the latter without bothering about the former, as though owning a sturdy tripod and a neutral density filter will do the trick.

I would gladly have talked about this with Ansel, Wynn and Henri too, but they gracelessly died long before I had the chance of discussing with them the idea of photographers using tracing paper.

Think of this essay as the third in a trilogy, my former writings on this matter being Coryphaei, Acolytes and Epigones and The Sincerest Form.

There is a story, possibly apocryphal, of Leonard Bernstein waking up one morning and saying to his wife, Felicia Montealegre, “I’m going to record the nine Beethoven symphonies.” Over her rejoinder that “von Karajan has already done that,” Bernstein went ahead. His recordings speak so clearly of his style, his brio, and his immense enthusiasm, which I like to think of as richly American.

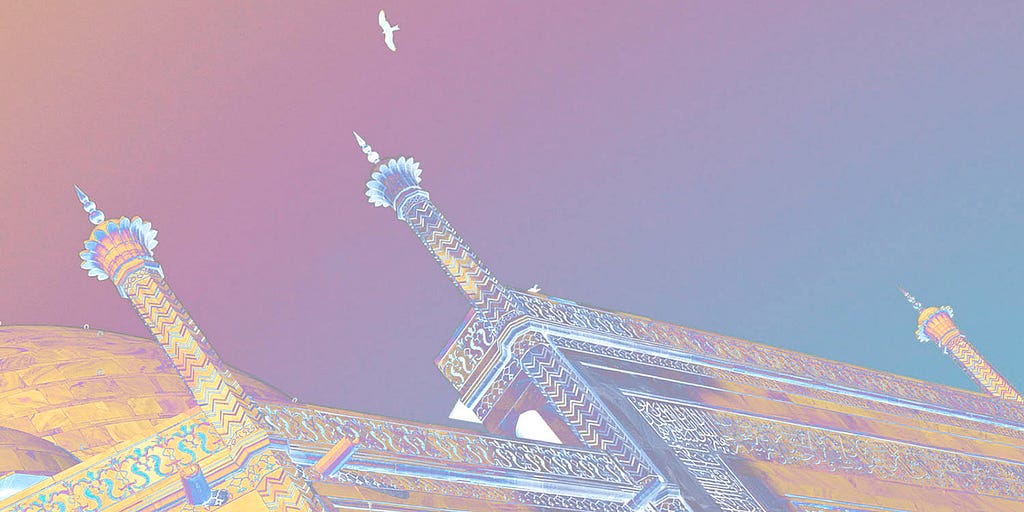

From time to time I see images of famous places, some made by photographers whose insight helped to make those places even more famous (Ansel Adams in Yosemite); some who used intelligence and imagination to give new perspectives and meanings. Unfortunately, there are too many others who, thinking themselves photographers rather than tourists, might as well have left their cameras at home and invested in postcards.

I love challenges, and so I remember the prospect of visiting the Taj Mahal for the first time. For weeks before, my dreams were dominated by what I could possibly do to put my own personal interpretation on photographing the world’s most photographed building. I found it less difficult than I had imagined, and much more pleasurable.

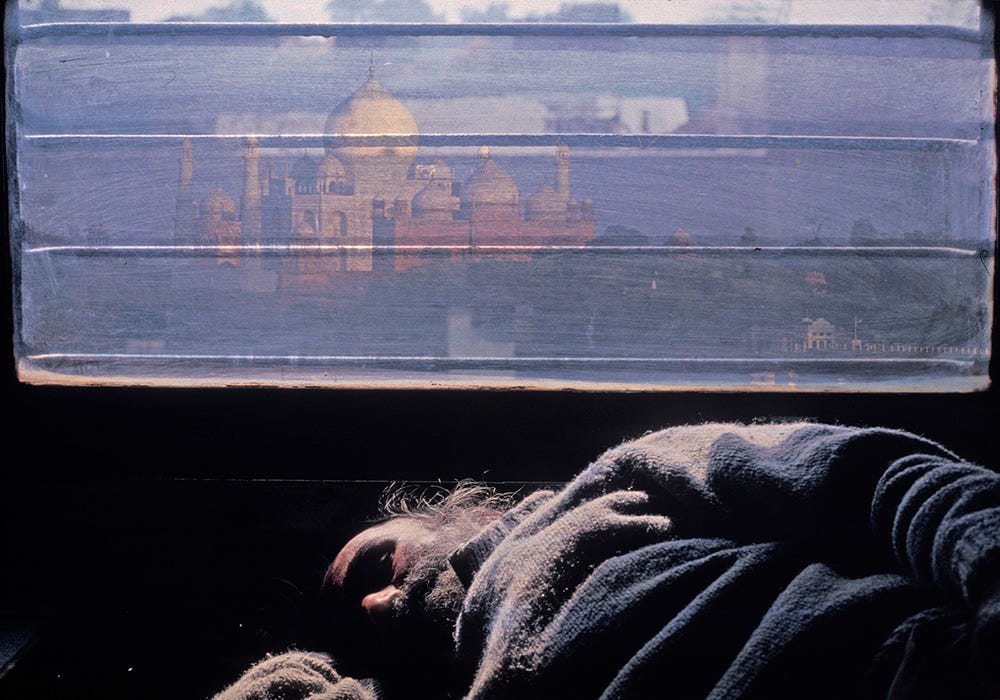

It took me a long time to discover that I am, in fact, a fictographer. Never satisfied with the representation of empirical reality, or the assumed realism of the photographic medium, I create my own versions of everything I photograph and add a fictive nature to my work. The moment of first exposure is never more than gathering primary raw material, the first step in being a storyteller.

My wife is a former professor of South Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. She and I, separately or together, have led tours to Nepal and India for various organizations, including the Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic. When I first told her of my anticipation of photographing the Taj, she responded much the way Felicia did to Lenny, but with the excellent intention of offering a challenge, not a discouragement. She has always known that my comfort zone lies in the discomfort of challenge. Yes, I had seen all those travel posters of an elaborate white-ish Muslim monument. I had no intention of re-re-re-recording it.

As it turned out, her work commitments prevented Karine from accompanying me, so I went alone and largely unschooled, except for what I managed to read in a guidebook. The first sight of the Taj Mahal was overwhelming, but I knew I could take my time, and do what I’ve always done, especially with an immobile subject: look, listen, feel, absorb, think, plan. Then interpret. Not that different from my portraiture of living, dynamic subjects, who enjoy the added benefit of conversation.

I believe in bringing as many senses to my imaging process as possible. For me the Taj Mahal was not only a visual fact, but also a mixture of history, romance, texture, culture, sounds, feelings, temperature and reverence. My first act was to leave my cameras in their bag, then approach the entrance of the building, and sit on the marble with eyes closed, touching the embossed surface of the building, listening to the multilingual voices around me, feeling the sun on my face, acknowledging the privilege of being there, and ignoring the tourists who thought I was blind. I had done that before, on the streets of San Francisco, where I had unintentionally left my hat upturned, thereby gathering coins from kind passersby for my train trip home.

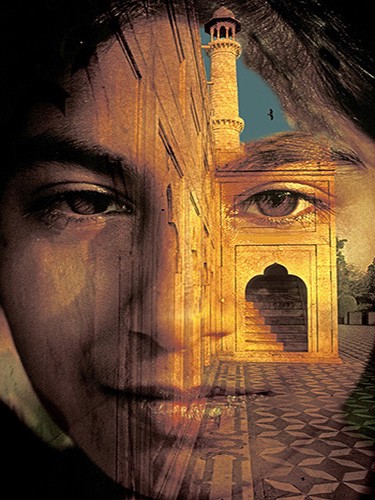

On the last afternoon of my first trip to India, I had gone to visit friends on the campus of Jawarhalal Nehru University, and found myself being followed by three young girls. I gave them a chocolate bar I had been keeping for the late night flight, and made an image of one of them. She had an elegant and solemn face for a twelve-year-old, and it’s her countenance that I later fused with the Taj, to make my Face of India, a Hindu child on a Muslim monument.

The other images, from a larger collection, follow.

Among my rewards for this work was a letter from a tour guide resident in Agra, who wrote “I’ve been taking tourists to the Taj for more than twenty years, but you’ve given me new ways to see and appreciate it.”

______________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on the creative process. He is a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain. He is known for the experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Find Your Own Path: Burn The Tracing Paper! was originally published in Midcentury Modern on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Post a new comment