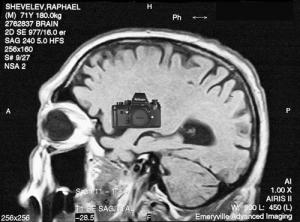

A friend who is a fine, accomplished and well-published poet recently stopped by. She looked at one of the pictures on the dining room wall and said "Photoshop?" I said "Cerebrum." Then I asked her what word processor she used to compose her poems. From her chastened look, I gathered the message had leaked through.

I continue to be dismayed at how many photography publications request, and print, details of photographers' equipment. Yet, I don't see literary magazines demanding and revealing the kind of pens, pencils, typewriters, paper, computers, printers, word processing programs used by their authors.

What is this fetish with mechanics all about?

What is this fetish with mechanics all about?

I think it is largely fueled by asking the delusional, wrong question: "How did you do this (so I can replicate your steps and show off my creativity?)" The right question might be "Why did you do this?" and other variations of inquiry about observation, interpretation, philosophy, mentation. I've been writing and lecturing about this for decades, but that’s a hint that the message hasn’t yet gone viral!

Even the world's oldest continuous photographic publication, the Journal of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, does this. When examining a photograph do I really give a laxative about which camera, lens or tripod was used?

A few months ago, the educated, cultured, and very personable Editor of the Journal called from Glasgow to interview me at some length on my portfolio Light and Recovery. Next month, the September issue will carry some of that work. We talked of the many, many things that go into making a portfolio of images and text, not the least of it being the intensely personal history and emotions involved.

Then, at the end of the call, she asked "What kind of equipment did you use?" I responded "Mostly my brain. Does that make me different?" Other than saturated cultural conditioning, there may have been practical, subtle, even entirely unconscious reasons for the question. The Journal carries quite a few advertisements from manufacturers and retailers, and I am aware of how vitally important that support is for a non-profit organization, known in the U.K. as a “charity.”

Less than a year ago I prevailed upon the Director-General of the Royal Photographic to terminate the Society's common practice of limiting entries to exhibitions and competitions on the basis of when the image was made. I did this for two principal reasons: unless dealing with the scholarship of especially precious, unique, or antique photographs, aesthetics should be the primary issue, not provenance; and because of technological innovation, a photograph can easily evolve and become a combination of several images made at different times. I’ve changed or added to photographs that first began their life on film more than thirty years ago. The Society used to request information on where the photographs were made, which makes not much more sense. Mine are commonly made north of my neck and in the region of our planet, though there are exceptions.

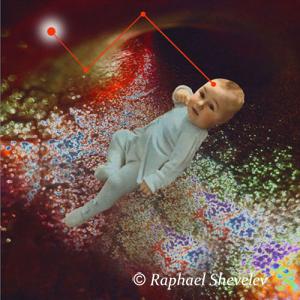

I originally arrived from outer space, you know.

I originally arrived from outer space, you know.

My first published photograph, a monochrome picture of runners at a high school track event, made it into a newspaper in Cape Town when I was a teenager. Even then I resisted numerical reductionism. When an editor insisted, I wrote 1/10,000 of a second at f64. I was astonished when they printed that. It didn’t have to make sense.

In previous lectures and publications I have talked about the analogy of teaching cooking by emphasizing organic ingredients, nutrition, health, presentation and sensual delight, without spending much time on the structure of a stove.

Recently I came across a short, pithy, and pointed article by Texas artist Jann Alexander "How to talk to a photographer like she's an artist." It’s a good read from a good artist. It must be good: she thinks the way I do.

At a reception in San Francisco some years ago, a senior Indian diplomat told me that the essence of photography is the direction in which you point the camera. He might have added that the essence of literature is in the choice of words. As a student and former professor of international relations, a similar riposte about diplomacy sprinted into my mind. Uncharacteristically, I was diplomatic enough to smile and keep my thoughts where my photography dwells: in my brain. But I confess that I took great comfort from the then-unexpressed thought that I knew much more about diplomacy than he did about photography.

As to equipment, I once insisted to a magazine editor that I wouldn't reveal the brand of camera I used until Nikon paid me for the advertisement.

_________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries

Comments

Now that I'm done smiling at

Now that I'm done smiling at your flip style (and I mean that as high praise), I'll add my two cents. Actually, they echo yours. Aren't we being asked by other photographers so that the creative matter in our brains can being replicated? And aren't editors inquiring so they can imply some higher knowledge of process to their readers? It doesn't make a lick how we made our art. What really matters is what it means to us, as creators, and to you, as viewers.

Thanks for a well-said needs-to-be-said post, Raphael. May this go virally out into the universe.

This article is wonderful!

This article is wonderful! Spot on! Thank you so much!

Post a new comment