On a unique occasion, before I entered elementary school, my mother spoke of her birthplace. She called it “Yelok,” the Yiddish form of Ylakiai. It was then a tiny village, a shtetl, in northwest Lithuania, with a population of less than one thousand. About half of them were Jewish. My mother’s family name was Abramson, her father, Simon. I don’t recall her mother’s name, and mother quietly refused any further inquiry. By the time I was a teenager, I realized that she was taking refuge from intense pain, and I didn’t pursue the subject. I know nothing about my maternal grandparents.

My mother, Dora, was orphaned early in her life. I believe there were five children, four girls, one boy. The eldest, a teenager named Esther, struggled to hold the remnants of the family together, and must have had help from the community. Eventually, as I’ve searched whatever traces of my childhood memory are available to piece the story together, the children were farmed out to foster parents. My mother somehow found her way across the nearby Latvian border to the coastal town of Libau (Liepaja), and found a home in the Shevelev family, whose second son Jacob, my mother’s age, later became my father. To my mother, the name “Esther” was sacred, and in recognition of this, it became part of my older daughter’s identity.

Of the family of five children, three survived the Holocaust: my mother, her older sister Tzila, and their brother Hershel, known for the rest of his life as “Abe,” his foreshortened surname. The others were murdered, though where and how I cannot say.

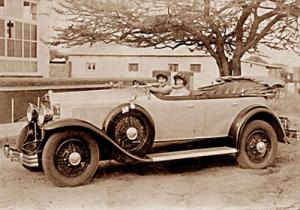

Uncle Abe was my favorite. He laughed a lot, and seemed to take a greater proportion of pleasure out of life than the other adults in my family. For a relatively recent immigrant to an obscure part of the African continent, he had done quite well for himself. He acquired an automobile dealership, a pleasant home in Windhoek, the capital of South West Africa (now Namibia) and a small sheep farm near Otjiwarongo. Of the few pictures I have of my mother, one has her seated behind the wheel of Uncle Abe’s Buick convertible, with my Aunt Tzila in the passenger seat, ca. 1930. I'm sure Abe must have taken this picture of his sisters. I believe he was interested in photography. He gave my mother the gift of a Voigtländer bellows camera, which, many years later, still unused, became my first.

Uncle Abe was my favorite. He laughed a lot, and seemed to take a greater proportion of pleasure out of life than the other adults in my family. For a relatively recent immigrant to an obscure part of the African continent, he had done quite well for himself. He acquired an automobile dealership, a pleasant home in Windhoek, the capital of South West Africa (now Namibia) and a small sheep farm near Otjiwarongo. Of the few pictures I have of my mother, one has her seated behind the wheel of Uncle Abe’s Buick convertible, with my Aunt Tzila in the passenger seat, ca. 1930. I'm sure Abe must have taken this picture of his sisters. I believe he was interested in photography. He gave my mother the gift of a Voigtländer bellows camera, which, many years later, still unused, became my first.

As I sift through my memories of his adventurous life, and of his appearance, I see a man whom I resembled in my forties and fifties. He listened to me, and engaged me much more than the others did. We were not only relatives. He was my first adult friend.

Abe was a freer spirit, a Freemason who married “out of the faith,” as I have, and couldn’t have cared less about what the rabbis might have thought of his eating bacon. Nor do I. His visits to Cape Town were happily anticipated, and he stayed with us except when on business. Then, he would find accommodation at the Assembly Hotel in Queen Victoria Street, not far from the House of Assembly, the lower chamber of Parliament. An invitation to dine at the hotel was my favorite treat (menus! choices!) and a real challenge for my kosher-observing parents. A shock greeted us on the first occasion. On a table just beyond the entrance to the dining room was a heavily decorated suckling pig. It was my first sight of a dead quadruped sucking an apple. Dad and mom sidled past, averting their eyes. As I followed behind, Abe whispered “It’s quite delicious.”

Uncle Abe became a special hero of mine on the only occasion I visited his home. That took a long overnight train journey north from Cape Town, to the town of Upington, on the banks of the Orange River. He and his African driver Jonathan came to fetch us in a grey Buick sedan. The five of us set out westward across dirt tracks and the desert, where the car bogged down in the sand. Not another soul in sight, as the adults all tried to free the car from the obstinate earth. But the wheels just spun, and we were trapped. I didn’t realize until later that being without food, water, or blankets for the desert night could be problematical.

After a brief consultation, Abe set off alone on foot, with a reassuringly firm stride. An anxious time passed before we saw a distant mirage, figures far away. As they got closer, we could make out Abe, an older bearded Herero tribesman, and two donkeys spanned together. I remember running toward them, and being lifted in Abe’s arms. Jonathan tied the donkeys to the front bumper and, with them pulling, all the adults pushing, the car was moved onto firmer ground. Uncle Abe gave the Herero some money, and I witnessed, for the first time, I believe, the lovely African politeness in which all gifts are accepted with both hands cupped, as though one hand were insufficient to bear the weight of the generosity.

The journey continued, until we encountered a barbed wire fence, interrupted by a wide metal gate across our track. On the other side, in our path, was a very large bovine. I, the city kid, assumed a bull, but in retrospect it may have been a cow, an enormous creature, staring at us. How would we negotiate our passage? Abe got out of the car, opened the gate, grabbed hold of the horns, and shoved the bull/cow out of the way. It must have been a cow. My uncle, my hero, twice on the same day.

The journey continued, until we encountered a barbed wire fence, interrupted by a wide metal gate across our track. On the other side, in our path, was a very large bovine. I, the city kid, assumed a bull, but in retrospect it may have been a cow, an enormous creature, staring at us. How would we negotiate our passage? Abe got out of the car, opened the gate, grabbed hold of the horns, and shoved the bull/cow out of the way. It must have been a cow. My uncle, my hero, twice on the same day.

More than sixty years later, in the hilltop fortress of Chittaurgarh, Rajasthan, a rather less fearsome Indian cow stood blocking my way. The needed solution was now part of family lore, so I grabbed its painted green horns and pushed. We Abramson-Shevelevs know what to do when faced by large beasts.

Late that night in Windhoek, my first encounter with Aunt Greta was less than pleasant, as were my second, third and fourth. It didn’t improve for the week we stayed there. She was tall, lean, dressed in clothes that matched her severity, brown hair pulled back in a bun. Their daughter, my cousin Lola, a year or two older than I, was much more fun, part of it the game of avoiding her mother’s ire. On my second day, we children were served canned plums. I hated their taste, and said so, whereupon Aunt Greta insisted I eat them, invoking “the starving children of Europe.” I didn’t obey, wondering how my food consumption could possibly help or hurt others, but the thought of starving children shocked me. Lola and I found a waxed paper bag, inserted the plums, in crayon addressed it to the starving children of Europe, walked down the block, and put it in the mailbox.

In the winter of 1949, I came home from school one day and found mother carving up a large fish in the kitchen. She was red-eyed with tears, struggling to control her sobbing, and the large blade in her hand. “Uncle Abe is very, very sick,” she said, trying to deny to herself as much as to me the truth of his death. Dad had left an hour before my arrival. He caught a flight to Windhoek on a South African Airways DC-3, and returned two or three days later, after the Masonic funeral.

In his will, Uncle Abe mentioned me. He left me fourteen lambs. The only place we could put them was on the concrete yard at the back of our flat, under the washing lines. I found string with which to secure the gate, then told Anita and Alice, the children of German Jewish refugees next door, that they could play with and feed the lambs. For a few weeks, whenever I heard the approach of a heavy vehicle, I’d rush to the window to see if my lambs were arriving. They never did.

So I didn’t benefit from Uncle Abe’s death. But all my life I have greatly benefited from his.

_________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Comments

I am in tears from the beauty

I am in tears from the beauty of your writing and memories! Do you realize how priceless these are? I will smile every time I see a sheep now, and a cow. I am able to imagine myself in every one of these stories, watching…they are so vivid. Beyond wonderful.

Dearest Raphael, This it one

Dearest Raphael,

This it one of the most beautiful, emotionally and visually rich stories I have ever read. You are so gifted as an artist and a writer, but most of all as a human being who sees and feels deeply. I shared it on my Manifeniger Books page hoping other people would get to enjoy it. The title did not alert me to how moved I would be. Thank you.

That's a poignant story.

That's a poignant story. Sometimes it takes just one

person to show that the walls don't have to be there.

As always, a remarkable piece

As always, a remarkable piece of writing about a beloved member of your memory-family. The image of the African gesture of thanks for a gift with both hands cupped is something that will always stay with me. Thank you, Raphael!

I am in complete agreement

I am in complete agreement with the other postings about your latest tale. It touched me profoundly, and I can't help smiling about your youthful innocence in the mailing of the plums to the starving children of Europe. You haven't changed in your humanity.

What more can I say, Raphael,

What more can I say, Raphael, than these most appreciative friends of yours and recipients of your amazing writings have already mentioned. I wholeheartedly agree with them. You are a wonderful storyteller with the skills and talent to express your life experiences in the most honest, erudite and literary way that engages the reader bringing forth empathetic emotions...thank you very much.

Post a new comment