On the Saturday before Rosh Hashanah in 1946, before my eighth birthday, I accompanied my parents to visit my only remaining grandparent, Blume-Devorah Westermann-Shevelev. The others had all died in Latvia and Lithuania before I was born. We lived in a flat on the lower slope of Table Mountain, with a view of the city and harbor. My paternal grandmother – bubbe – lived in the vibrant suburb of Sea Point, two or three blocks from the oceanfront, from which one can see Robben Island. It took two bus rides to get to her home, the first down the hill into the center of Cape Town, the second westward to the Sea Point Main Road, a busy commercial avenue. The bus stopped at the corner of St. John’s Road, and we’d alight to walk a block to a very modest four-flat building. We didn’t yet have our first car.

Grandmother lived on the left, downstairs, in a tiny two-bedroom unit. She had to put coins in the meter to generate the gas for cooking. I liked standing on a chair to help her with that. The smaller of the two bedrooms was occupied by uncle David, my father’s youngest sibling. The two men hadn’t talked to each other for years and wouldn’t ever again. During our visits, uncle David would sequester himself in his room, and I’d knock to gain entry. I liked him, and in retrospect, given the unexpected direction of my own life, perhaps it was because he sketched so well. He was then the only member of the family with an interest in art and classical music. Years later, when I was a student at the University of Cape Town, I asked each of the brothers what their feud was about. Neither could quite remember, but that wasn’t the point.

Anyway, on that Saturday, grandmother gave me her usual treat: a sixpence so I could walk back to the corner of Main Road, and buy a packet of potato chips in which a small twist of paper held the salt. When I returned, the adults (sans uncle David) were conversing in Yiddish. I joined in.

It must have been late in the morning, close to noon, when we heard the postman arrive. Grandmother rose to retrieve the mail, and when she came back, her faced reflected foreboding. In her hand, among other items, was an envelope marked with the emblem of the Red Cross. She sat slowly, and clearly without willing, opened it. Inside was another envelope, addressed to her. She recognized the script.

During the Second World War, the Red Cross made prodigious efforts to ensure deliveries of foodstuffs and mail to prisoners of war and, when possible, prisoners of the German concentration camps. Occasionally, perhaps once a year, those confined would be permitted to write a very brief censored letter to relatives on the “other side.” By the end of the war, a huge quantity of mail had been accumulated, and now, in the second year of the peace, it was being distributed. The letter was from her first child, my oldest uncle, Moses. It had been written several years earlier, before he was murdered in Majdanek.

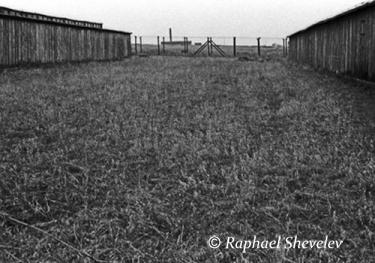

Moses Shevelev was born, I believe, in 1908. As a young man, he had left the family home in Libau (Lepaja), Latvia, and found his way to Paris, where he attended the Faculty of Law at the University of Paris (Sorbonne), and practiced as an attorney until the German conquest of France. The French authorities, pre-empting their German overlords, rushed to detain and deport Jews. Uncle Moses was put onto a train. The destination was Majdanek, on the edge of the eastern Polish city of Lublin. Unlike other camps, Majdanek was not screened from public view. It was right there, the fence also demarcating the border of Polish farmers’ smallholdings, as it still does. Shots and screams from the camp must surely have penetrated the air, as did the stench from the crematorium.

Moses Shevelev was born, I believe, in 1908. As a young man, he had left the family home in Libau (Lepaja), Latvia, and found his way to Paris, where he attended the Faculty of Law at the University of Paris (Sorbonne), and practiced as an attorney until the German conquest of France. The French authorities, pre-empting their German overlords, rushed to detain and deport Jews. Uncle Moses was put onto a train. The destination was Majdanek, on the edge of the eastern Polish city of Lublin. Unlike other camps, Majdanek was not screened from public view. It was right there, the fence also demarcating the border of Polish farmers’ smallholdings, as it still does. Shots and screams from the camp must surely have penetrated the air, as did the stench from the crematorium.

Grandmother, my parents and I sat in silence. She had certainly known - or guessed - that her son was dead. We sat there for a long time. The adults said nothing, and I knew enough not to ask.

Just before the war broke out in September 1939, my father and his brother, my uncle Max, also settled in Cape Town, made a determined effort to extract Moses from France. With their considerable diligence, and certainly bribes to officials, the offer of a visa to Madagascar came through. The telegraphed response from uncle Moses lives with me still: “I don’t want to be stranded on a remote island.”

Among the small items that have accompanied me to homes on the other side of the world is a photograph made in the early 1920s. It shows four of my grandmother’s five children. David was either an infant or not yet born. Those depicted are, in ascending order of age, Helena, who, as a very young woman emigrated to Palestine, Max with his left hand on a toy wooden horse, my father Jacob (Jack), and Moses.

In 1994 that photograph accompanied me to another place: Majdanek.

I found a niche in the wall across from the ovens, and photographed the photograph there. Karine and I were doing the research for what would later become my book, Liberating the Ghosts: Photographs and Text from the March of the Living. (LensWork:1996). The book is dedicated to two men: my uncle, and a French Huguenot called Daniel Trocmé. Both were murdered in Majdanek.

I found a niche in the wall across from the ovens, and photographed the photograph there. Karine and I were doing the research for what would later become my book, Liberating the Ghosts: Photographs and Text from the March of the Living. (LensWork:1996). The book is dedicated to two men: my uncle, and a French Huguenot called Daniel Trocmé. Both were murdered in Majdanek.

On Easter Monday, 1994, we took a short bus ride to the camp, and found ourselves alone in that vast, cold, depressing place. Taking shelter in one of the huts, we lit two votive candles on the concrete floor. One was for uncle Moses. The other was in memory of Daniel Trocmé, from the French village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, where Karine had lived as a child. Daniel ran a children’s home in which he’d hidden Jewish refugees and supplied them with false papers. When German soldiers raided the home and took the Jewish kids, Daniel insisted on accompanying “his” children. We later discovered that, by an astonishing coincidence, we’d been in the camp precisely on the fiftieth anniversary of Daniel’s death.

Perhaps the two men had met and gotten to know each other.

The letter is long gone, though I wish I’d been able to preserve it. It may have been written in Yiddish, though Moses and his siblings were all also schooled in Hebrew, German, Latvian, and, of course, he was Francophone. Perhaps the letter had been written in German, to pass the censors.

I don’t know whether Moses ever married and fathered children. Many years ago I would fantasize about finding long lost French cousins. But the story, though it continues to haunt me, ends with the letter. It was the beginning of my consciousness.

_________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries.

Comments

What a story! You are such a

What a story! You are such a gifted writer. I could feel myself being there when the letter came. You took a story that could have happened to millions and made it so personal, yet universal.

A very poignant piece. Thank

A very poignant piece. Thank you for sharing this very personal story.

That has every element of a

That has every element of a great and tragic story. You need to send it to the New Yorker or another magazine of that caliber. It needs to be read by many people. Thank you for writing it.

Thank you for sharing this,

Thank you for sharing this, Raphael.

Riveting! I was

Riveting! I was there...feeling that we have a long way to go as a humanity...and suffering with you from the tragedy of a failing community...

A moving vignette from the

A moving vignette from the perspective of an 7 year old that really brought home the

horrors of the Holocaust to an average Jewish family.

A wonderful, family-defined

A wonderful, family-defined story. It seems to glow especially at two points (besides the opening of the letter itself): the refusal of Moses to be 'stranded on an island', and the last sentence, that it was the beginning of your consciousness. I loved the details of standing on a chair to help your grandmother put the coins in the meter for gas!, and the bag of crisps with its separate twisted paper of salt. There's something about that salt…Thank you, Raphael!

Thank you, Raphael, for this

Thank you, Raphael, for this moving history. There are a million stories. I have in front of me now, a picture of my Hungarian grandfather and one of his 12 children, plus the Christian men of his village of Kunsziget where my father was raised. When I went to visit the village in 1978, I went into a cafe in this one-horse town and saw people who looked like those in the photograph. One older man came up to me and said, (in Hungarian), "Oh my god, this must be Bela's daughter because you look exactly like your grandmother Rose." And told us the story of how the priest in the town hid my grandparents until a month before the end of the war when the German soldiers were marching through the town and someone said there were Jews hidden in that house. They threatened to kill the priest, so my grandparents gave themselves up and were murdered. I remember my father crying when he got the message. The son in the photograph was my uncle Feri, who was a boxer. In a bout in France, he was hit in the head and became deaf, so that when the German soldiers told him to stop as he walked through the woods in Kunsziget, he did not hear them so was shot.

Beautiful, beautiful. Thanks

Beautiful, beautiful.

Thanks for sending it.

Such a powerful story. Your

Such a powerful story. Your memories, details, and fantastic writing never cease to amaze me.

I was so moved by The

I was so moved by The Letter----I wish I could express how it impacted me---the summary of what everyone else had written would be a good start.

The best yet, Dad. Not only

The best yet, Dad. Not only are the feelings conveyed entirely authentic, but your style transports the reader to that very time and place with you. Thanks again for sharing your/our history so poignantly.

Beautiful, Dad. It really

Beautiful, Dad. It really gives me a sense of what it was like for you.

Thank you for sharing these

Thank you for sharing these very moving and precious memoirs Raphael.

Post a new comment