By my third night in India, I was exhausted, though my entry had been gentled by calmer days in Nepal. After dinner I walked slowly back to my tent, and sat down heavily on the cot. I was in Pushkar for the annual camel fair, staying in the brightly colored tents supplied for foreign guests, wondering what I was doing in the middle of the Rajasthan desert, among thousands of camels and even more people. Conversation, and sometimes thought, were drowned out by the shattering volume of gigantic loudspeakers sending a strange mixture of modernized devotional chant and Indian movie music directly, so it seemed, into that formerly private space between my ears.

I hadn’t really done much strenuous exercise, nor had I exerted my creative powers with pen and camera beyond their limits, yet I felt as if I had climbed a Himalayan peak while writing a thickly philosophical work, and the time had come to relax and enjoy the peace of labors well done. I just hadn’t done that much. I managed to pull off my clothes and slide into a gritty bed — the fine sand gets into everything — and, staring upward, listening to the noise, I found the explanation: Image Assault, the photographer’s particular dimension of sensory overload.

For every waking moment in India, and I suspect many sleeping ones, I had been subjected to the cacophony of color, the blur of sound, the taste of the air, all wrapped in an inescapable gigantic bubble of frenetic, often unpredictable movement. At times it was like being locked inside a Catherine-wheel to which some infinitely well meaning holy man had applied a match, and where the peculiarly western sense of exact time had no relevance. It was the climactic, full moon night of the mela (festival) and I had simply lost myself in one of the many, many Indias.

Earlier that evening, as I had walked across the dunes to my camp, trying to escape the crowds and the loudspeakers, the red desert sun was touching the earth on my left, and on my right a camel’s head was haloed for a moment in the center of the rising moon. I walked among the nomad families preparing for the night, waving to them as though I were an expansive Lawrence at another time, in another desert land, living out the fantasy of going each day from one age to another, compounding the onslaughts of the five senses and the three dimensions with the hesitant uncertainty of the fourth. Later, an Indian friend would bring light, but no relief, by telling me, “We live in several centuries at the same time.” At Pushkar it could have been millennia.

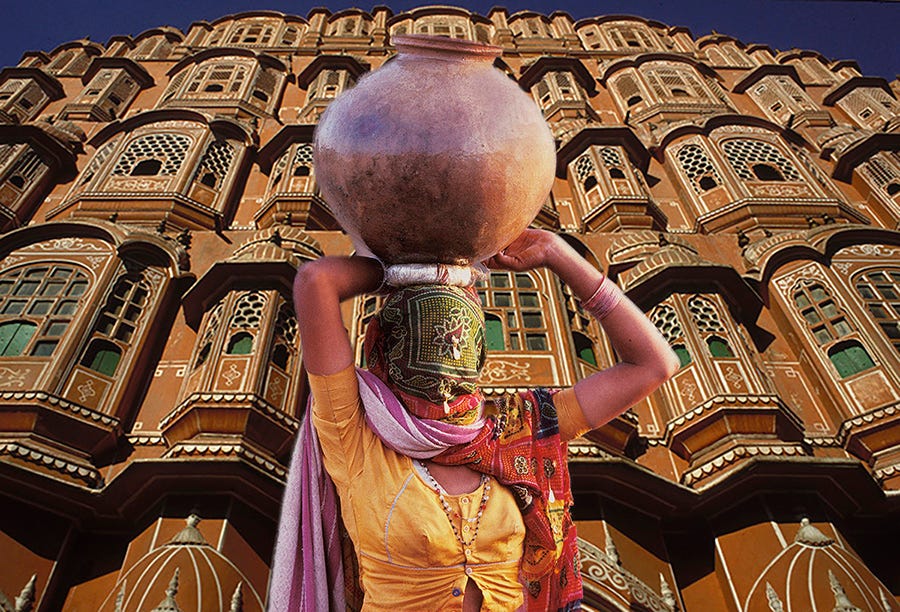

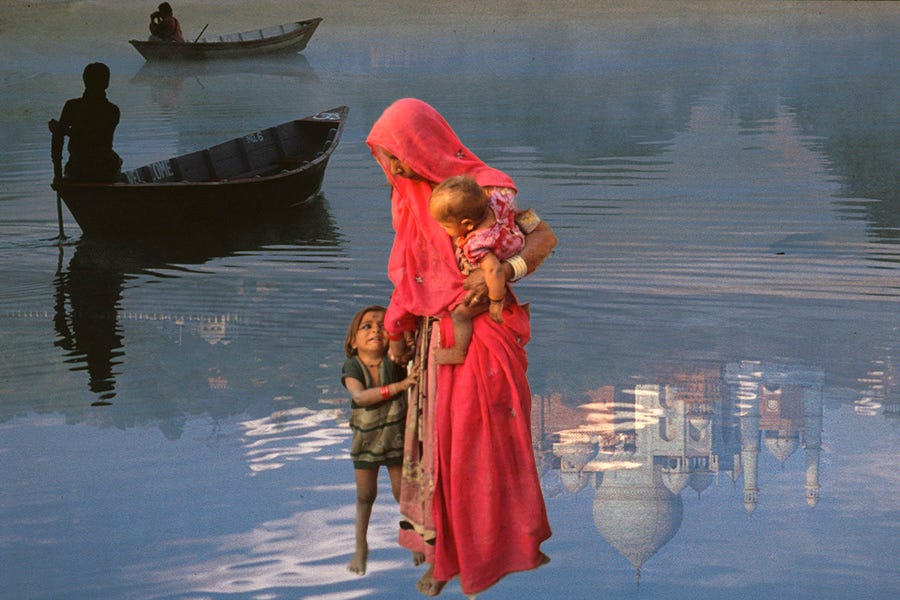

And so it continued without respite, through the Rajasthan countryside, Jaipur’s palaces, Amber’s Hall of Mirrors, Jodhpur’s medieval blue-painted Brahmapuri quarter, Agra’s Taj Mahal, Varanasi’s holy Ganges, each but a splendid setting for the cascade of people, and many more people, their often brilliant costumes, their movement, their sounds, their occupations and devotions, and sometimes, at rarer moments, their quiet meditations; and everywhere, the startling gamut of the faces of India, the faces that, even in their fluid transition, gave foundations, meaning and permanence to the artistic, architectural and topographical monuments.

This is a photographer’s paradise, a place to immerse oneself without restraint, without watch or calendar, to allow oneself the thrilling luxury of making images because they also sound, feel, taste and smell intriguing. And if you have given yourself unreservedly to all those senses, and to your sensibilities, your photographs will likely look intriguing, too.

When I had returned with my many images to the accustomed sensory safety of my home in California, I discovered that many of my photographs were good expressions of sensually special moments, each caught from among so many rich others. But it was equally true that this medium’s clever separation of each moment from all others denied me, by its simplicity, the very metaphor by which I was seeking to convey the layerings of images that fell upon me, constantly teasing my eyes and my brain.

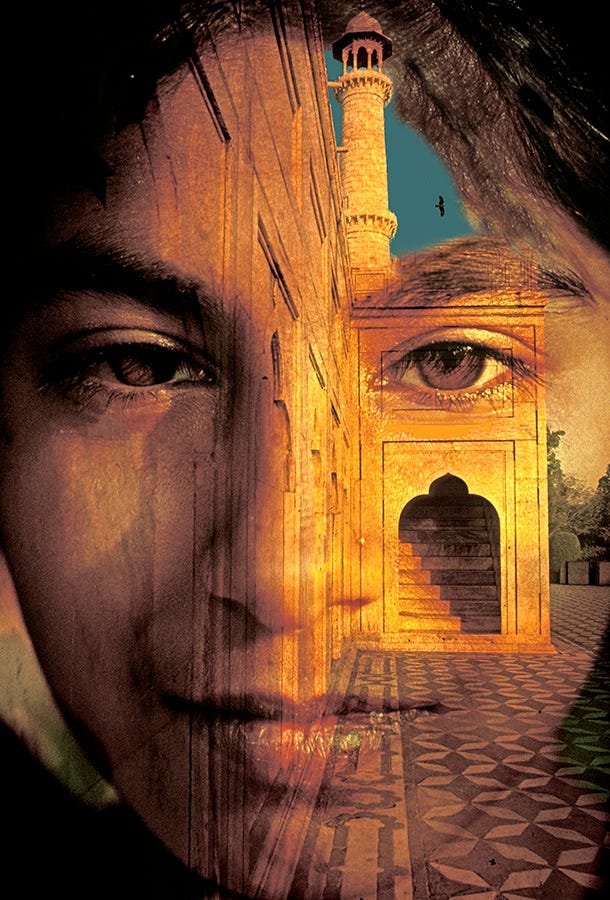

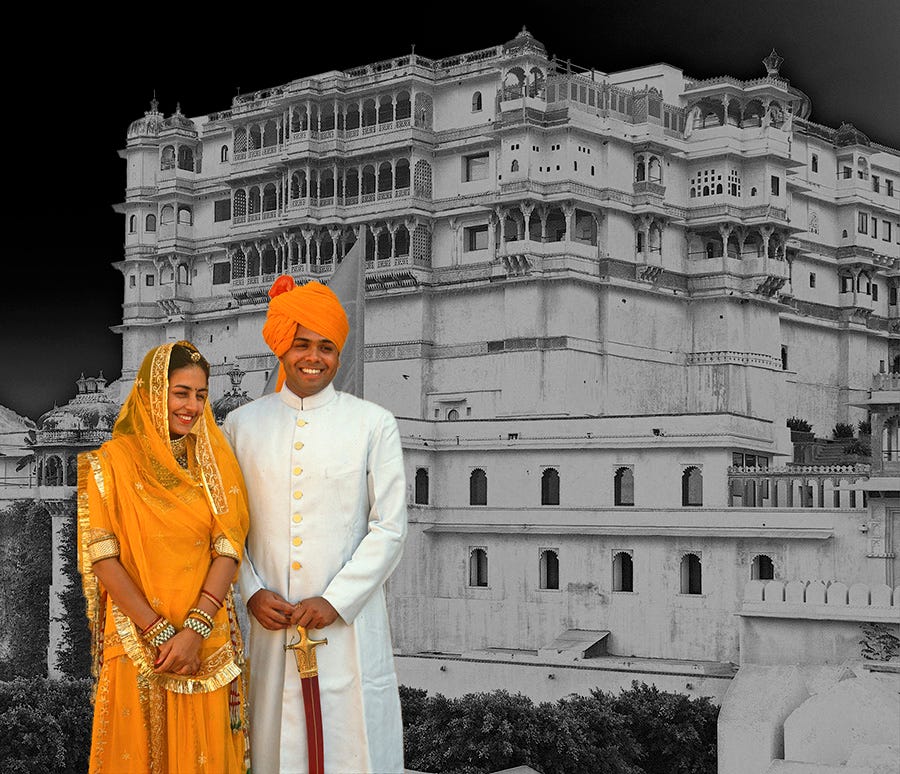

In all my rational western life, and my experience as a photographer, my brain had been trained to separate each image, the marbled architecture from the beautiful child whose precociously serious gaze had so distracted me, the palace from the handsome features of a young Rajput noble couple, the Taj Mahal reflected in the Yamuna from the Bishnoi mother and children, the Red Fort of Agra from the sacred cow, the veiled village water carrier from the Royal Hawa Mahal in Jaipur.

Try as I might, my consciousness and my conscience rebelled at seeing these elements as unrelated, each bounded by discrete vision and the exclusive format of the frame. So I conspired to rejoin them — let no camera put them asunder — to let my senses and my mind again play with multiple visions, and allow me to conjecture what I might do when next I returned to India, and whether to do it by premeditated design, by subsequent synthesis, by both, or not at all. But I now know for certain that our visions and our memories, even with a camera, do not have to be bounded by the single objective moment.

_________________________________________________________

© Raphael Shevelev. All Rights Reserved. Permission to reprint is granted provided the article, copyright and byline are printed intact, with all links visible and made live if distributed in electronic form.

Raphael Shevelev, FRPS, is a California based fine art photographer, digital artist and writer on photography and the creative process. He is known for the wide and experimental range of his art, and an aesthetic that emphasizes strong design, metaphor and story. His photographic images can be seen and purchased at www.raphaelshevelev.com/galleries

INDIA: LAYERED MEMORIES was originally published in Click the Shutter on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Post a new comment